by Jessica Sartiani and Tom Hopkinson

Regular readers will know that at Barista Hustle, we put a lot of importance on keeping your burrs clean, sharp, and well-aligned. Sharp burrs allow us to make coffee that is extracted higher and tastes better, and we recommend changing grinder burrs much more frequently than manufacturer’s claims would suggest.

There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence, but surprisingly little published research on the effect of grinder burrs going blunt. What research exists mainly looks at burrs that are very heavily worn, and at the end of their manufacturer’s recommended life. We usually prefer to replace burrs well before that time, however — as little as halfway through their maximum recommended lifespan. For this reason, we wanted to look a bit more into what happens to burrs during the stage in between.

To see what happens to the coffee when burrs are only lightly worn, Jessica Sartiani carried out some experiments for us, comparing the results from new and lightly-used burrs in a cupping. We found that a difference in flavour appears well before any measurable effect in either extraction or grind size distribution can be detected.

In this video, BH coach Jessica Sartiani explains the experiment and describes her findings.

Why Worn Burrs Make Worse Coffee

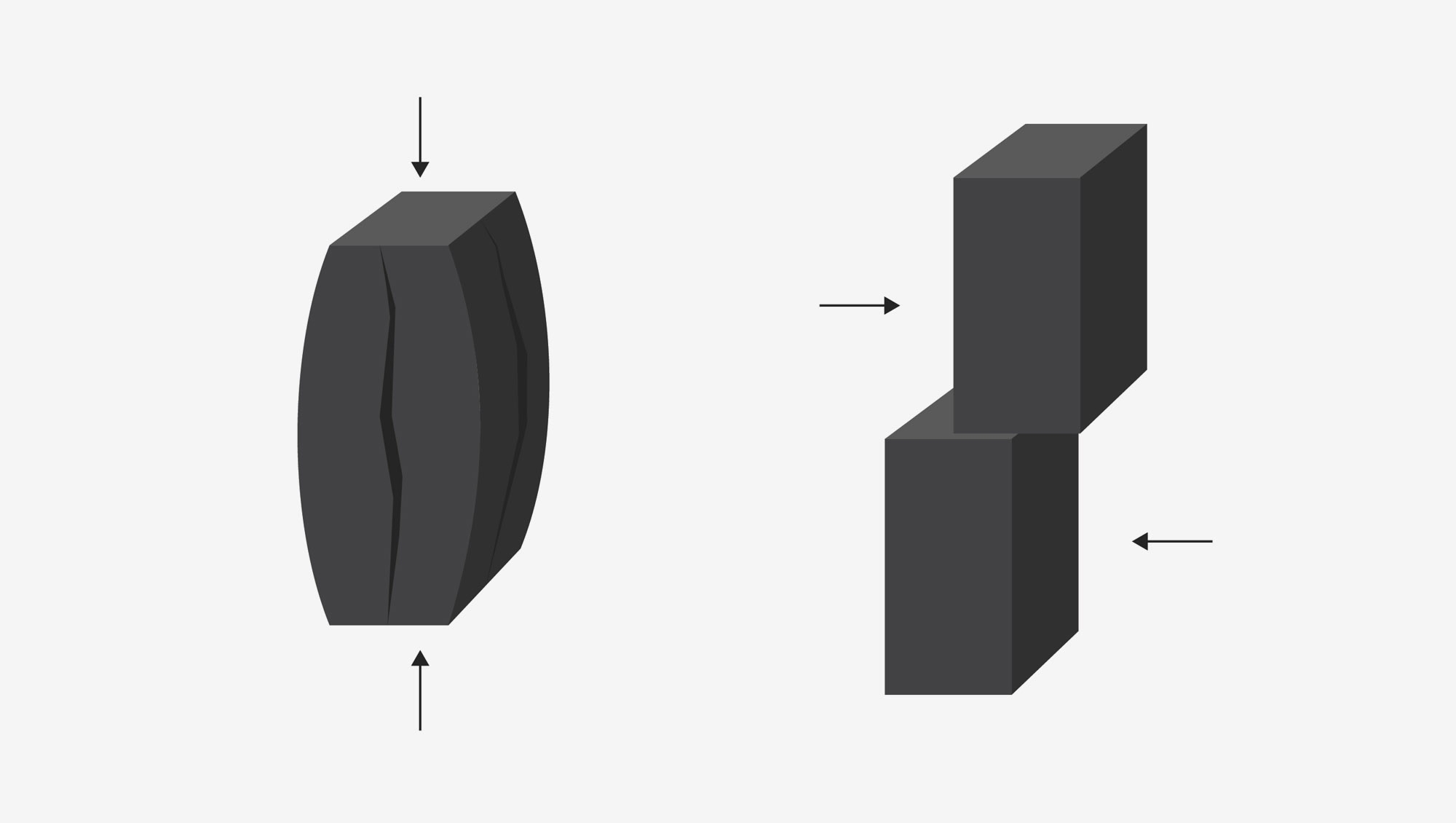

When burrs are sharp, the cutting edges moving past each other act like a pair of scissors on the beans, cutting them into pieces. This cutting action is called ‘shear’, and breaks beans into relatively evenly-sized pieces. The best grinders use mainly shear forces to produce ground coffee particles of even size and shape. Evenly ground coffee generally makes for even extraction, and even extraction makes for better-tasting coffee.

Blunt burrs, on the other hand, tend to crush beans rather than cut them. This type of force is called ‘compression’, and when coffee particles are subjected to compression they tend to shatter into lots of different-sized pieces including larger chunks (boulders) and tiny fragments (fines). The less-even spread of grind sizes from blunt burrs leads to less-even extraction, and less tasty coffee.

Compression (left) and shear (right).

Compression (left) and shear (right).

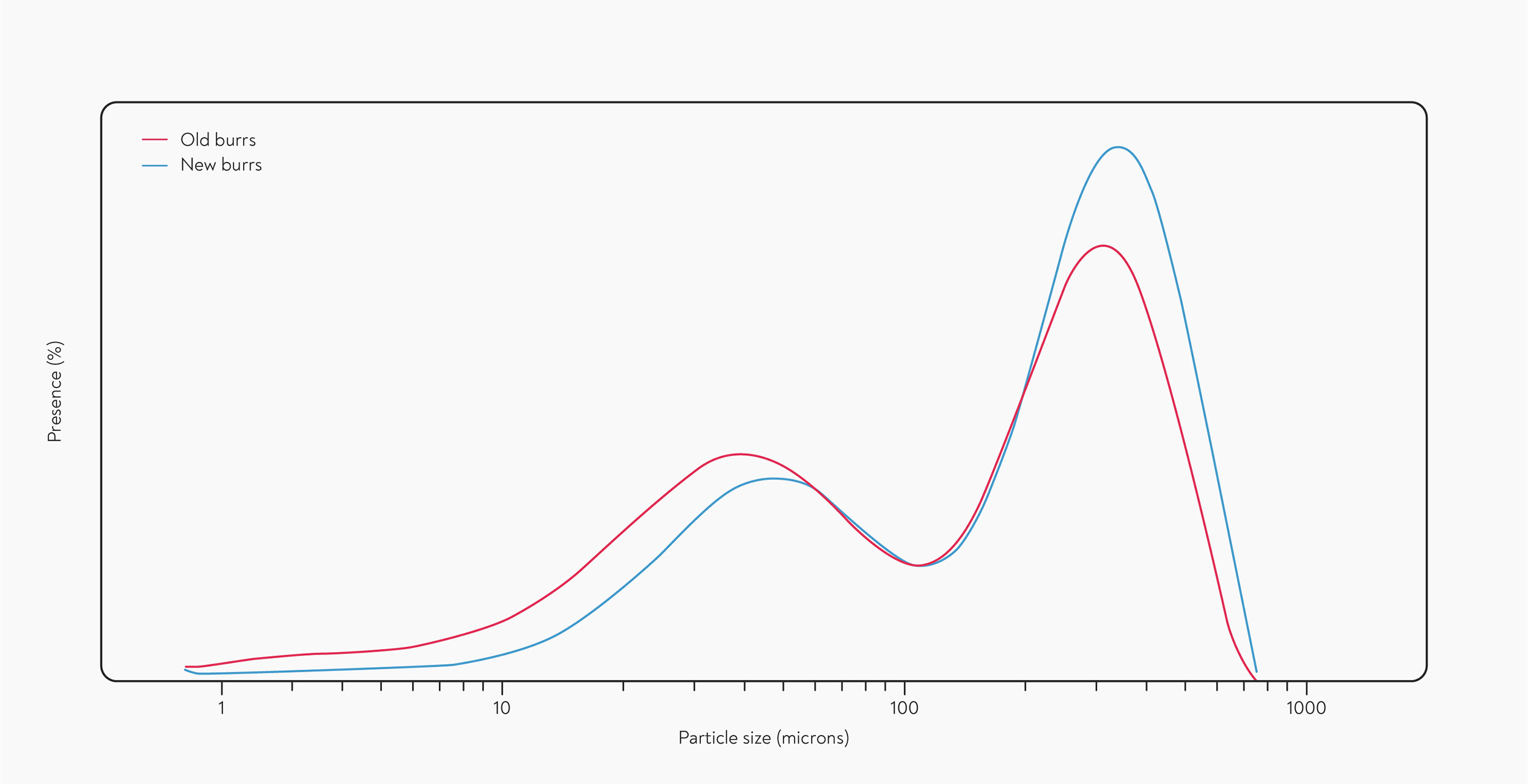

Research in espresso brewing shows that it’s possible to achieve higher extractions with sharp burrs. A study comparing K30 burrs before and after grinding around 600 kg of coffee found that the new burrs produced much fewer fines. 600kg is close to the manufacturer’s recommended maximum for these burrs, and when the burrs are this worn, baristas will have to grind coarser, on average, to achieve the same shot time (Griffiths et al 2018).

Grind particle size distribution from a K30 grinder with new burrs (blue) and after grinding approx 600kg (red). Adapted from (Griffiths et al 2018).

Grind particle size distribution from a K30 grinder with new burrs (blue) and after grinding approx 600kg (red). Adapted from (Griffiths et al 2018).

Another experiment by Socratic Coffee (2015) took a different approach, dialing in an espresso by taste, and then measuring the resulting extraction. Since this experiment doesn’t use a fixed grinder setting, but relies on taste, it can be seen as a measure of the extraction ceiling (the highest extraction achievable without astringency and bitterness). They compared new burrs, and burrs that had been used to grind 1,500kg of coffee, and found that the sharp burrs allowed them to achieve significantly higher extractions, once the espresso was dialled in.

Extraction and Particle Size

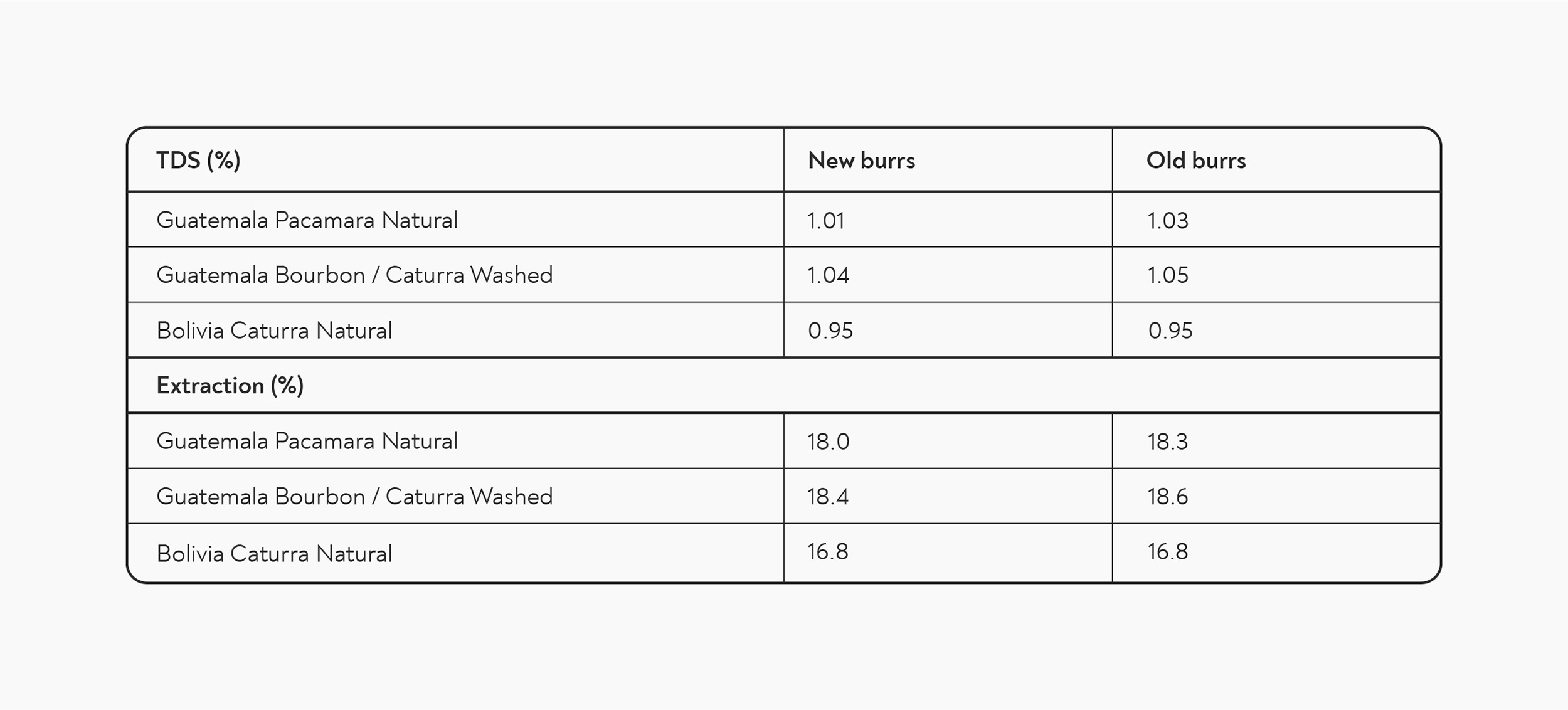

We cupped three different coffees, ground in an EK43 with either new, seasoned burrs, or burrs that had been used to grind an estimated 300kg of coffee, at the same grind setting. This amount of wear is just a fraction of the manufacturer’s recommended lifespan of up to 6,000kg, and is well before the point that even the most quality-focused coffee shop would consider changing the burrs for this type of grinder.

We tasted and measured the extraction of three cups of each coffee with each set of burrs. A statistical test (two-way ANOVA) showed that while there was a significant difference between different coffees, the old and new burrs had no significant effect in terms of extraction.

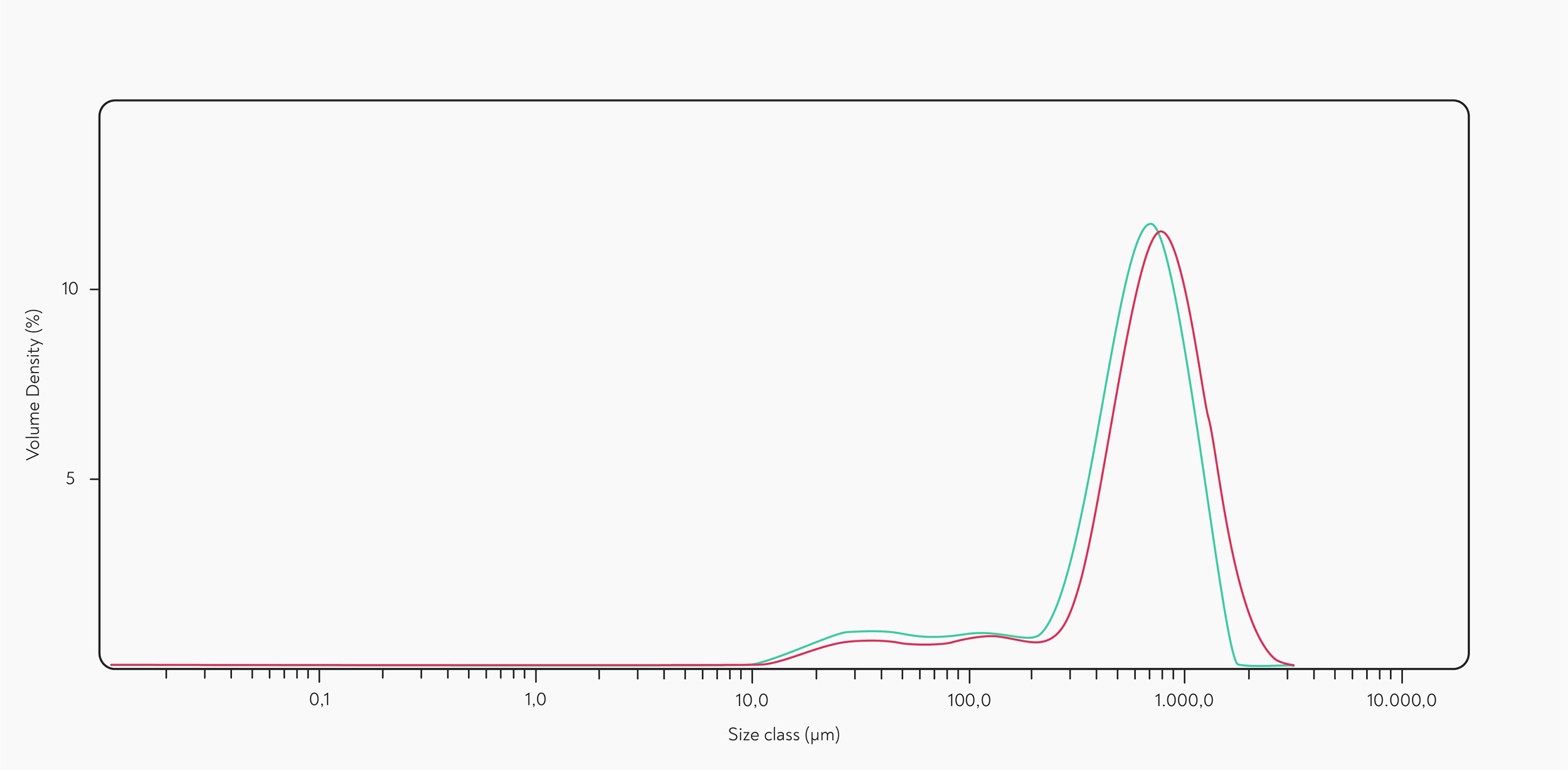

We also sent samples from each coffee to be analysed in a laser diffractometer with the kind help of Francesco Sanapo, founder of the legendary Ditta Artigianale in Florence, Italy. The results were similarly inconclusive: while the main peak is shifted slightly to the right (possibly indicating a slightly larger gap between these burrs), the size of the two peaks is virtually identical, and there is no visible difference in the amount of fines produced.

Particle size distribution of coffee ground in an EK43 with new burrs (green) and after 300kg (red). This graph is representative of the results from all coffees sampled.

Particle size distribution of coffee ground in an EK43 with new burrs (green) and after 300kg (red). This graph is representative of the results from all coffees sampled.

Compare this graph to the one from Griffiths et al (2018) above: with burrs showing signs of wear, the peak for fines would be expected to be higher, and the main peak lower, compared to new burrs.

Taste Tests

Where we did find a noticeable difference, however, was in terms of taste. Most cups were decidedly better when ground with the new burrs, with both the Guatemalan washed and the Bolivian natural coffees having a more intense aroma and more clarity of flavour when cupped with the new burrs. The new burrs made the coffees sweeter, cleaner, and brighter, with a fuller body. The exception was the Guatemalan natural Pacamara, which tasted weak and lacked acidity, with an unpleasant bitterness that Sartiani suspects could be some kind of roasting defect that was less perceptible when ground with the older burr set.

These striking differences, despite no measurable differences in extraction or particle size distribution, suggest that we could benefit from being more open-minded about how we decide on when a burr set is past its best. Subjective indicators of wear such as taste and body are hard to measure, especially over a long period of time, compared to TDS or particle size. However, such subjective measures could pick up differences that don’t show up in more objective tests. Since we only had time to test one pair of burr sets, and only installed and aligned them once each, it’s possible that the differences we tasted resulted from some minor flaw in alignment or burr manufacturing, rather than wear, however.

Extraction and particle size distribution are widely considered the most objective measures for determining the amount of wear on grinder burrs. Measuring extraction has been recommended as the best method by Socratic Coffee (2015), Rao (2013), and others; meanwhile, when writing about industrial coffee grinding, Blittersdorff and Klatt (2017) maintain that ‘the best way to control the wear of the grinding rolls is monitoring of the fines’. This experiment reminds us, however, that even though these objective measures are becoming more and more accessible to baristas and roasters, our palates can still pick up on differences that can’t yet be measured.

0 Comments