‘This coffee has a pronounced malic quality, that gives way to a tartaric حموضة as it cools…’

If you’ve attended a Brewers’ Cup competition, you’ve probably heard some variation of this speech. You might even be familiar with the taste of some of the organic acids commonly found in coffee — citric, malic, lactic, acetic — and confident that you can tell them apart in a blind tasting.

Baristas presenting a coffee to competition judges often use individual organic acids as flavour descriptors

Baristas presenting a coffee to competition judges often use individual organic acids as flavour descriptors

New research published this week, however, suggests that the levels of many of the organic acids found in brewed coffee are so low as to be essentially undetectable (Birke Rune et al 2023). The findings suggest that the type of حموضة you taste in your coffee depends on more than just what acids are present. In other words, if you taste a ‘malic حموضة’ in your coffee, it’s most likely not only malic acid that you’re tasting.

Morten Münchow and Ida Steen from CoffeeMind teamed up with researchers from the University of Southern Denmark to investigate how much of the acids that we like to name-drop are actually present in brewed coffee. They also tested whether coffee professionals can taste the difference between citric and tartaric acid in a brew. Their findings challenge a lot of the assumptions we make about how the different acids in coffee affect the flavour.

They found that, at the levels of acid typically found in brewed coffee, coffee professionals weren’t able to correctly identify any of the organic acids in a taste test. In fact, for acetic, lactic, and malic acids, the levels found in the coffee they brewed were so low that they were below the detection threshold, i.e. they can’t be detected at all.

According to the researchers, their findings call into question the methods widely used throughout specialty coffee for training and testing sensory skills. Even for lightly-roasted, specialty beans, the levels of most organic acids found in the brewed coffee are much lower than the levels used in the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) and Coffee Quality Institute (CQI)’s sensory tests, for example.

In a further upset to our preconceived ideas about حموضة, the researchers found the lowest pH — and the highest concentration of citric acid — in the Brazilian coffees they tested. The Kenyan coffees, meanwhile, had less citric acid and a higher pH, despite the fact that most of us baristas would consider Kenyan coffees to have a very high perceived حموضة.

The Acid Tests

The standard protocol for testing the ability to taste acids in coffee, used by both the SCA and the CQI, is to ‘spike’ brewed coffee with organic acids. The SCA uses citric, malic, lactic, and tartaric acids in the test for Sensory Skills Professional, while CQI tests citric, malic, acetic, and phosphoric acids as part of the Q grader exam.

Acidity is an important part of every grading system for coffee

In each case, trainers add 0.4 grams of each acid to a litre of brewed coffee (or 0.5 grams in the case of lactic acid). For the CQI course, the trainer spikes two cups out of four and asks students to spot which two cups have the acid added (the ‘matched pairs’ test). The SCA qualification goes a step further, by testing the ability of students to identify which acid has been added.

The intention of the tests is that the amount of acid added should be detectable — in fact, the SCA instructions explicitly tell the trainer to ‘adjust to taste’ if necessary, to ensure that students will be able to taste the difference between the cups.

However, with the exception of citric acid, the researchers found that the concentration of each of these acids is much lower in brewed coffee than the level used in the SCA and CQI tests. They tested five different specialty coffees: two Brazilian pulped naturals, two Kenyan washed coffees, and one washed coffee from Bolivia. For each coffee, they tested three different roast levels, within the lighter range of roasts common to specialty coffee.

Light roasted, specialty coffee should be pretty acidic — but out of the acids tested by CQI and SCA protocols, only citric acid reached the level (0.4 grams per litre) used in the tests. Two other important acids — chlorogenic and quinic acid — were present in higher concentrations, but their contribution to flavour is still being debated, and they are not included in common sensory tests.

The Detection Threshold

Sensory tests for حموضة are based on the assumption that common organic acids have a significant effect on the coffee’s flavour, and help distinguish different coffees. But many of those acids are undetectable at the low concentrations found in brewed coffee.

The researchers spiked brewed coffee with different amounts of each acid, and tested them on a group of coffee professionals — in this case, bar managers from renowned Copenhagen roastery Coffee Collective, all of whom had had previous training on recognising organic acids, as well as an intensive 30 minute training immediately before taking the test.

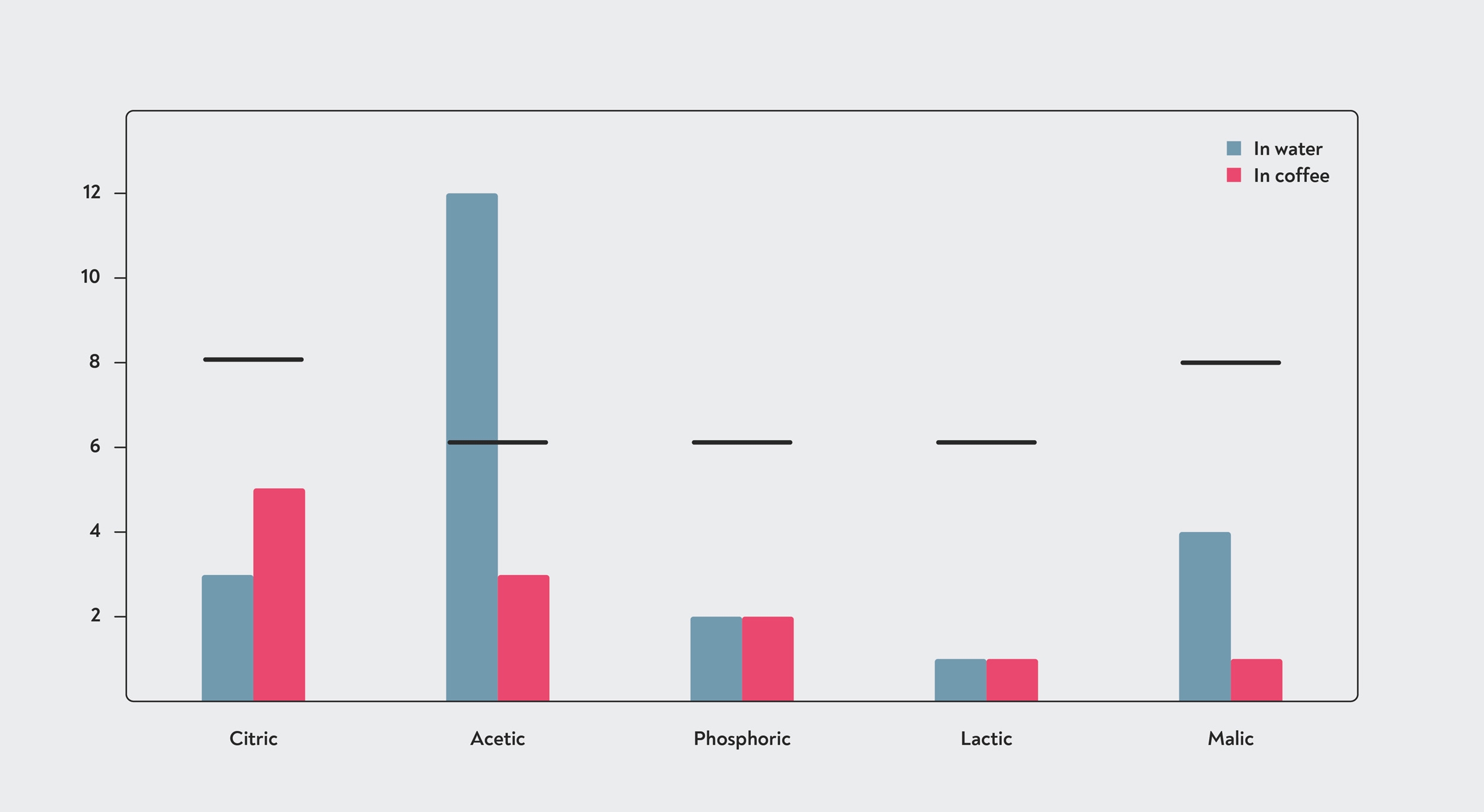

They found that at the concentrations found in coffee, the baristas could not identify which acid was which in the tests. In fact, for most of the acids it was not even possible to detect that any acid had been added at all. When tasting acids in plain water, rather than in brewed coffee, the tasters fared little better — only correctly identifying acetic acid.

Recognising acids in water and coffee. The tasting panel were unable to recognise any of the acids at the typical concentrations found in coffee. In water, they were able to identify acetic acid, but none of the other acids commonly tested. The black bar indicates the number of correct answers required for a statistically significant result.

Recognising acids in water and coffee. The tasting panel were unable to recognise any of the acids at the typical concentrations found in coffee. In water, they were able to identify acetic acid, but none of the other acids commonly tested. The black bar indicates the number of correct answers required for a statistically significant result.

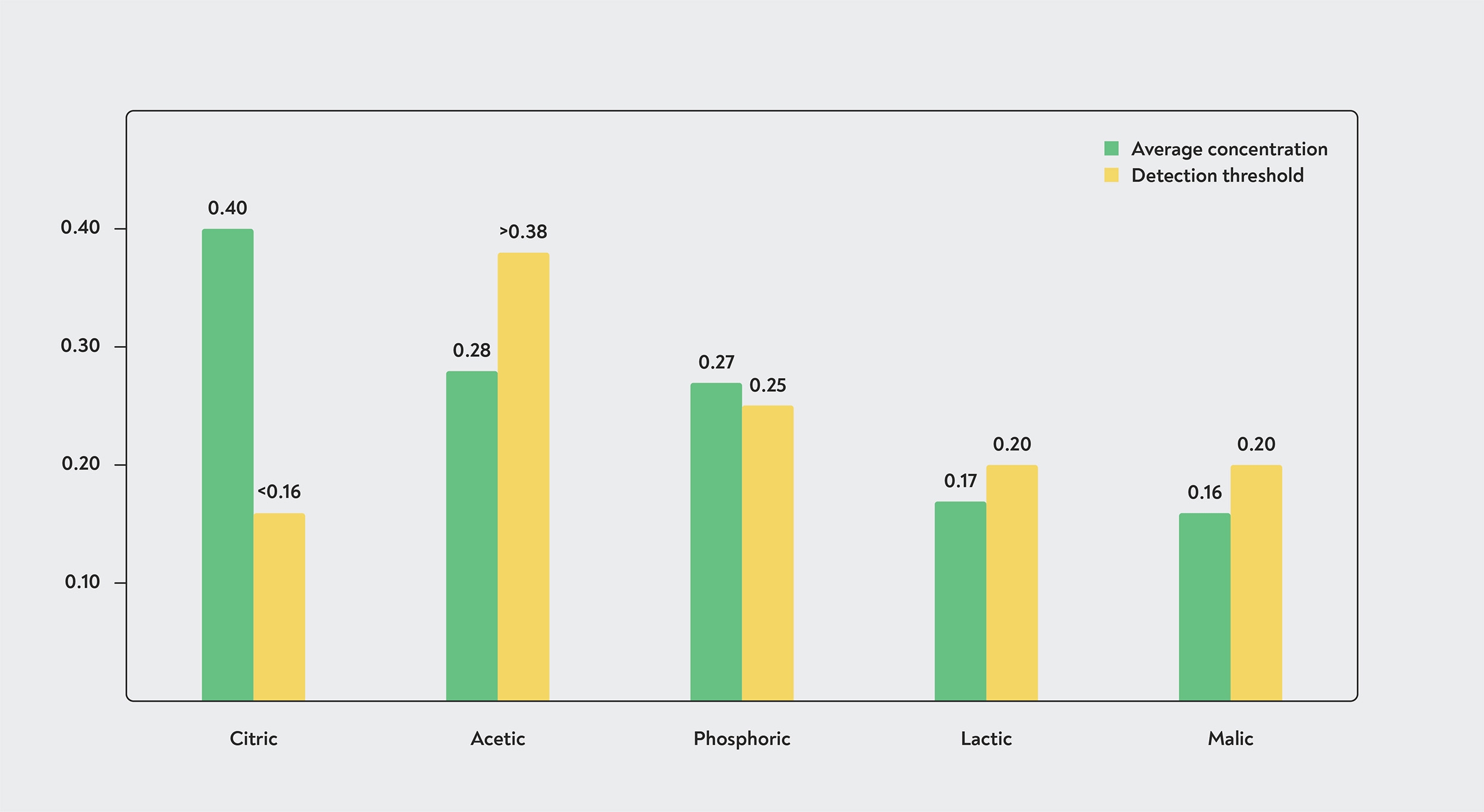

By adding different amounts of each acid to coffee, the researchers calculated the amount they needed to add to coffee in order for a cup difference to become detectable — the ‘detection threshold’. According to their results, the average concentration of malic, lactic, and acetic acid in brewed coffee is below that threshold, while the average concentration of phosphoric acid was just barely above it. The only acid that was clearly detectable, at the concentrations found in coffee, was citric acid.

The concentration of some of the important organic acids in brewed coffee is below the detection threshold. The green bars indicate the concentration found in coffee brewed in a French press, and the orange bars indicate the amount of each acid that needed to be added before the barista could taste the difference.

The concentration of some of the important organic acids in brewed coffee is below the detection threshold. The green bars indicate the concentration found in coffee brewed in a French press, and the orange bars indicate the amount of each acid that needed to be added before the barista could taste the difference.

These results contradict the idea that variation in the concentration of individual organic acids determine the flavour of a coffee. Spiking coffee with extra acid in this way doubles the concentration of the acid, and yet the difference is not even perceptible.

Since most acids in brewed coffee are below the detection threshold, it’s impossible to taste them individually, the authors say. In a vlog announcing the research, Morten claims

“Training, teaching, and testing students [on those acids] is not relevant and is a waste of everybody’s time.”

On the other hand, Joseph Rivera, who co-developed the CQI course, points out that only the SCA course requires students to identify individual acids. “I think the study was well done and comprehensive,” he says. “However, the biggest issue is that nowhere in the Q course, nor in my course [the Coffee Science Certificate (CSC)], do we grade students on their ability to identify each individual acid.”

“There is a blank line [in the CQI and CSC tests] where students can write in their guess on acid, but it’s not part of the final grading,” he adds. “For me as an instructor, I find it is more important that students understand the underlying chemistry than grade their sensorial abilities.”

What About Brew Strength?

In the CoffeeMind study, the researchers brewed each cup using a French press, to a strength of around 1.1% TDS, because they considered it to be the method most similar to cupping, used for sensory evaluations.

Since this is somewhat weaker than the coffee most people drink, does that mean that the acids would be more easy to spot in a stronger coffee? After all, the way that the coffee is brewed has a strong effect on the حموضة: In terms of both titratable حموضة and perceived sourness, brewing parameters make nearly as much of a difference as roast level (Batali et al 2021).

However, simply increasing the total strength of the brew doesn’t necessarily mean that the acids in it would then be higher than the detection threshold. Firstly, the detection threshold in the paper is specific to the brew strength they use — in other words, it’s the amount of acid that can be tasted in that coffee.

A stronger brew could well have an even higher detection threshold, since the concentration of all of the other compounds in the brew would also increase, making it harder to taste the contribution of any individual acid.

For example, imagine trying to taste a small amount of acid spiked into an espresso, compared with the same amount of acid added to weak filter coffee. The added acid is most likely a lot harder to taste in the espresso — in other words, the detection threshold in a stronger coffee is probably even higher.

That said, choosing French press as the brewing method does add one complication, Rivera points out: “French press coffee has a much higher content of oils, الميلانويدين, and microparticles that enhance شعور الفم and can ultimately ‘mask’ particular nuances.” In the SCA and CQI tests, by contrast, the tastings are based on filter coffee.

What Makes Coffee Acidic?

In this study, the Kenyan coffees had the highest pH — in other words, they were the least acidic. This is surprising when you consider the typical flavour of Kenyan coffee, but it’s not the first time researchers have found similar results. For example, one research group found that Kenyan coffees had less citric acid but more malic acid than Central American coffees (Balzer 2001). Another found that East African coffees in general had a higher pH than Central American ones (Brollo et al 2008).

Not all acids contribute equally to the perceived حموضة of a coffee. The perceived حموضة of a coffee — in other words, how acidic it tastes — seems to correlate more to the ‘titratable حموضة’ rather than the pH or total acid concentration of a coffee (Batali et al 2021). Titratable حموضة is a measure of how much alkali you need to add to neutralise all of the acid in a coffee. Some compounds in coffee can buffer the حموضة, meaning that changes in the concentration of some acids may have only small effects on the pH. Astute readers of our Water Course will notice that this is the same concept as القلوية العالية., but in reverse.

The precise combination of acids present can also affect the flavour: for example, citric acid and malic acid have a synergistic effect. Combined, they taste more sour and more astringent than either acid does by itself (Rubico and McDaniel 1992). On the other hand, bitter-tasting compounds such as quinic acid may mask some of the حموضة of a coffee. The Brazilian coffees in the CoffeeMind study contained more quinic acid, which could partially explain why they have lower perceived حموضة (Birke Rune et al 2023).

One interesting study also suggests that our perception of the حموضة of a coffee is affected by the coffee’s aroma (Brollo et al 2008). In this study, researchers also found that Kenyan coffee had a higher pH and lower titratable حموضة than Central American coffee, despite the fact that Kenyan coffee is usually considered more acidic.

However, when they asked their tasting panel to wear nose clips to block the aroma of the coffee, the متذوقي القهوة rated the Kenyan coffee as lower in perceived حموضة than the other coffees — in line with the measurements of pH and titratable حموضة. The researchers suggest that the aromas of Kenyan coffee might be partly responsible for its high perceived حموضة — in other words, a citrusy aroma makes a coffee seem more acidic than it really is, while caramel aromas can decrease the perception of حموضة and make coffee taste sweeter. Tasters may even simply recognise the aromas of a Kenyan coffee and be primed to expect high حموضة (Brollo et al 2008).

This may be similar to how we perceive sweetness in coffee: most coffees do not contain enough sugar for the sweet taste to be detectable; instead, it’s more likely that the perception of sweetness comes from aromas in the coffee associated with sweetness, such as caramel or vanilla.

Acids are Not Only Acidic

The acid content of a coffee doesn’t only affect the حموضة. Some acids found in coffee have recognisable aromas, such as the well-known vinegar aroma of acetic acid, or the burnt caramel notes of pyruvic acid. Many acids can also contribute bitterness or اللاذع to coffee, or even act as flavour modulators, changing the flavour of the coffee even when they have no substantial flavour of their own (Yeager et al 2021).

Chlorogenic acids, meanwhile, can break down in the brewed coffee, changing the effect that they have on flavour over time. Batch brew aficionados will already know about this effect from our دورة الترشيح: chlorogenic acids in coffee break down during storage, increasing the coffee’s harsh, sour, and bitter qualities.

When coffee is stored for long periods, some of its acids break down, changing the flavour.

When coffee is stored for long periods, some of its acids break down, changing the flavour.

Chlorogenic acids in coffee are sometimes associated with sour flavours, and sometimes with bitter or metallic notes. It may be that chlorogenic acids have little flavour of their own, and rather it’s the جزيئات formed by chlorogenic acids breaking down that explain their effect on the flavour of coffee (Yeager et al 2021).

What Acids Can Tell Us

This research makes it clear that it’s not the concentrations of different acids that determine the difference in flavour of coffees from different origins. The high perceived حموضة of a Kenyan coffee, for example, doesn’t only depend on the acids it contains. Meanwhile, factors such as the roast level or the processing method seem to have a bigger effect on the acid content of a coffee than geographical origin does.

Do these results mean that the concept behind the SCA and CQI tests is fundamentally flawed?

It’s worth noting that the tasters in this study were not Q graders themselves. It’s possible that the training involved in certification by the CQI (or SCA) would allow tasters to detect and even identify the acids at lower concentrations. The tasters in this study are nonetheless experienced coffee professionals, and this suggests that the tests are not applicable to most of the industry, Münchow argues. “They are skilled متذوقي القهوة. If it’s not relevant for them, with their education and career path, it’s not relevant generally.”

On the other hand, the حموضة of coffee is an important component of its overall quality, and strongly linked to how much customers enjoy it (Yeager et al 2021). The industry needs a way to calibrate on حموضة in order to be able to grade a coffee’s perceived حموضة in a meaningful way.

It’s clear that the ideal test for this would include a more holistic approach to حموضة, that takes into account the different factors affecting perceived حموضة. Until such a test is devised, however, spiking coffee with organic acids could still help calibrate متذوقي القهوة in terms of how they describe حموضة — even if it is in no way representative of the concentrations found in brewed coffee.

In the meantime, though, perhaps it’s time to reconsider descriptors such as ‘malic حموضة’, which sound scientific but don’t reflect the reality of how we taste coffee. Even though حموضة is measurable, how we perceive حموضة is highly subjective. A descriptor like ‘green apple حموضة’ accounts for this — and would make a lot more sense to our customers.

Hello, I would like to ask you about the reaction mechanism of acid in the mouth. For example, the tongue root muscle contraction and so on, because just started to learn and limited site, can not be in-depth understanding

Is it feasible that the perceived acidity of Kenyan coffee is caused by the higher TDS with pour over brewing compared to Central and South American coffees that have measurably higher acid content? I’m assuming that the higher perceived acidity of titratable acidity compared to ph alone needs the release of protons in the more alkaline oral environment for receptor activation of the sourness .Fascinating stuff

Hi Kenneth, TDS could indeed be a factor. In the CoffeeMind study they controlled TDS but didn’t measure the perceived acidity of their brews. I don’t know of a study that measures perceived acidity of different origins under controlled TDS conditions.

Some studies suggest that the total sourness isn’t only the result of acids disassociating in saliva, but that (protonated) acids can cross the cell membrane – for more detail on what we know, take a look at https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-physiol-060121-041637

We can ^taste* the weak organics as they stimulate the receptor yet we can’t distinguish them and present in sub threshold quantity.! Thanks for this provocative lesson Need to ponder further with a tasty Kenyan

This article is great, appreciated, and somewhat timely for me since I’ve been doing research and consulting with other scientists on malic vs citric acid perception (outside of coffee).

Thank you! We’d love to hear more about that if there’s anything you can share